About our work

We are broadly interested in understanding how protein machinery facilitates the biochemistry of the cell. Our model system is photosynthetic CO2 fixation, a complex set of reactions that must occur in the right place and time to capture and convert light into stored chemical energy. Photosynthesis is uniquely important for human society. It catalyzes the assimilation of inorganic carbon into the organic world and is the ultimate source of nearly all nutritional calories on Earth, as well as many of society’s fuels and materials. Our long-term goal is to adapt and engineer photosynthesis in planta for improved carbon assimilation and yield.

We employ several model organisms including various microbes and plant species to study photosynthesis. Much of our effort has focused on the bacterial Carbon dioxide Concentrating Mechanism (CCM), a multi-component system that functions to increase the rate and specificity of the critical enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase / oxygenase (Rubisco). We use the tools of biochemistry, molecular biology, and synthetic biology to identify and characterize the key players and mechanistic principles underlying CCM function. In ongoing work, we are exploring how these tools and mechanistic insight can be used to improve photosynthetic CO2 fixation in plants.

We are also interested in the development of novel genome editing technologies for accelerating plant genetic experiments. Traditional plant biotechnology pipelines are slow and resource-intensive. To overcome this bottleneck, we are engineering novel genome editing proteins and delivery systems that are specifically engineered for plant applications. In the future, we believe such precision genome editing approaches can enable targeted genetic screens, testing hypotheses, and, ultimately, bringing improved traits into the field. Our specific areas of research are as follows.

Mechanisms and Engineering in the Biochemistry of CO2

Systems model of the CCM adapted from Mangan et al. 2016

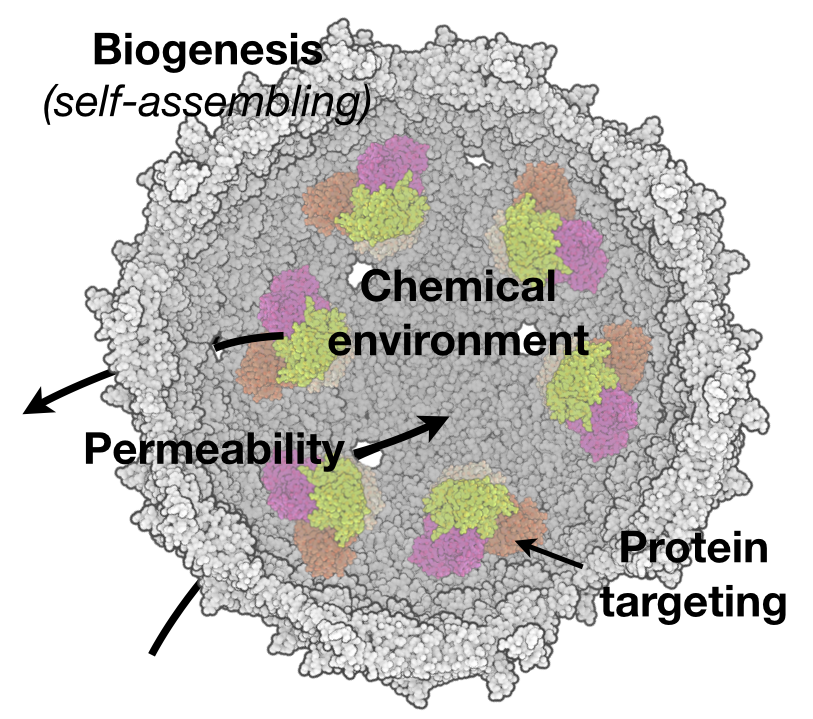

We are broadly interested in the biochemistry of CO2 assimilation and investigate the structure, function and engineering of enzymes involved in CO2 metabolism. The majority of carbon on the planet is assimilated into biological systems by the enzyme rubisco, and much of our work has focused on specialized CO2 Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) that have evolved to improve rubisco function. For example, many bacteria use a protein organelle, called the carboxysome, to provide a high CO2 microenvironment around rubisco as a means of improving rate and specificity. We have studied how this massive complex self-assembles and functions in the context of the cellular milieu. This includes a systems model of the CCM to better understand the many biochemical parameters, such as pH, carbon transport, and carboxysome permeability, that combine for efficient rubisco function (Mangan et al. 2016). Experimentally, we have used biochemistry and cell biological assays to map out protein-protein interactions in the carboxysome and how the size and homogeneity of the complex emerges from underlying elemental interactions (Oltrogge et al. 2024, Turnsek 2023).

We are also interested in genetic systems to explore, in a synthetic biological context, how efficient CO2 assimilation can be engineered de novo. We have used high-throughput screening strategies to identify unknown components of the CCM (Desmarais et al. 2019), and have demonstrated a complete reconstitution of the CCM by porting it from a native to a heterologous host (Flamholz et al. 2020). This was the first such successful demonstration of a fully functional, engineered CCM. Most recently, we have used these same genetic systems to carry out deep mutational scan of rubisco and reveal how even single mutations can positively alter the enzyme kinetic parameters of rubisco (Prywes et al. 2025). We are now using this approach to identify novel mutations which will have utility in planta.

Genome Editing Technology development

Insertional profiling of functional hotspots in the Cas9 protein (red denotes enriched, blue depleted) from Oakes et al. 2016.

An important application of our protein engineering work is to make robust genome editing that can be delivered to the right cell at the right time. For example, the study of many model organisms, particularly plants, is constrained by our ability to quickly and easily manipulate gene sequence and gene expression. Although advances with CRISPR-Cas proteins, such as Cas9, have accelerated this progress, much remains to be done. To this end, we have developed engineered variants of Cas9 that are allosterically regulated (Oakes et al. 2016) and have optimized the scaffold of Cas9 using topological mutagenesis in order to improve both delivery (Oakes et al. 2019) and for effector fusions such as base editors (Huang et al. 2019). Relatedly, we have also developed a technique, called MISER, that enables the directed evolution of smaller genome editing proteins which are more suitable for viral delivery vectors (Shams et al. 2021). Finally, we are applying these approaches to engineer variants of CRISPR and CRISPR-like proteins that are specifically engineered for applications in plant biology (Thornton and Weissman et al. 2025).

Tools for Protein Engineering

Domain insertion libraries can be used to engineer proteins with highly novel functions, with a variety of downstream applications.

Our group takes an integrative view of protein function. That is, we are interested not only in protein mechanism but also in trying to understand this mechanism in its native, cellular context. We therefore also develop genetic tools to interrogate proteins in the cell. Much of this effort has been focused on leveraging recent advances in DNA sequencing to interrogate protein function in higher throughput and also demonstrating that protein sequence topology is a critical, yet often unexplored, dimension of the sequence-function landscape (Higgins and Savage 2017). Highlights of our work include developing a novel systematic mutagenesis method (Higgins et al. 2017), a transposon-based method for rapidly constructing metabolite biosensors (Nadler et al. 2016), and development of an allosterically regulated Cas9 variant (Oakes et al. 2016). In more recent work, we have also developed a technique, called MISER, that enables the directed evolution of smaller proteins from a starting parental scaffold (Shams et al. 2021). Currently, we are developing high-throughput selective assays for some of our favorite enzymes, such as rubisco and carbonic anhydrase (Flamholz et al. 2020, Prywes et al. 2025), and working with collaborators, including the laboratory of Jenn Listgarten, to apply modern mutational methods and machine learning approaches to better explore sequence-function landscapes (Xiong et al. 2025).

Understanding the Diversity and Functions of Protein Compartments

The carboxysome is a 250 MDa+ complex formed from thousands of proteins, yet it self-assembles in the bacterial cytosol into monodisperse particles. How does this amazing process occur? In previous work, we have used microscopy to demonstrate the importance of carboxysome partitioning during cell division and the surprising connection between this process and the bacterial cytoskeleton (Savage et al. 2010; Yokoo et al. 2015). More recently we have focused on assembly directly and have demonstrated the minimal set of proteins sufficient to produce the carboxysome in a heterologous host (Bonacci et al. 2012), and honed in on one of these proteins, CsoS2, as particularly critical to the process (Chaijarasphong et al. 2016). We are now currently building on these advances to understand how specific protein-protein interactions direct the assembly process and are attempting to elucidate the fundamental biophysical principles leading to high fidelity assembly. Finally, we now believe that the carboxysome is yet one example of myriad ways in which protein compartments can facilitate biochemical function (Nichols et al. 2017). We are thus also interested identifying novel compartments and, more broadly, understanding the functional principles of compartmentalization. An example of the former is our recent identification and characterization of a wide variety of compartments involved in sulfur metabolism (Nichols et al. 2021).

Note that plasmid reagents from the Savage Lab are available from our addgene site and that all source code from our work is available on our github site.

About Cal

The Savage Lab is a member of the Department of Molecular & Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. UC Berkeley, also affectionately known as Cal, is a public research university dedicated to both education and research and has made such varied contributions to society as the discovery of six chemical elements and the birth of the Free Speech Movement. Cal is located near downtown Berkeley, California and is rooted in the vibrant intellectual, cultural, environmental, culinary, and entrepreneurial communities of the San Francisco Bay area.

The Savage Lab is also a member of the Innovative Genomics Institute (aka the IGI), a collaboration between UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco. This collaboration of diverse expertise seeks to develop genome editing technology and apply it for the public good in biomedical science and agriculture. The IGI is located in the IGI Building (IGIB), a 113,000 square foot research building on the northwest corner of campus adjacent to downtown Berkeley. The IGIB houses laboratories from numerous departments on campus and possesses state-of the art research facilities.